Unveiling Meliponiculture: Decolonizing Maya Stingless Beekeeping in the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico

Unveiling Meliponiculture: Decolonizing Maya Stingless Beekeeping in the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico

[Fig.1] This is a ko’olel káab stingless bee (Melipona beecheii) protecting the sole entrance of the beehive. Stingless bees have different roles throughout their lifetime. As guardian protector of her family, some Maya stingless beekeepers call her Balam Kaab Photo: Veronica Briseño Castrejon

Introduction

Maya Stingless Beekeeping is an ancient and ancestral practice [1,2] that integrates ecological knowledge linked intrinsically with Maya traditional dwellings, milpa crops, and native species of the tropical forest in the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico. Such heritage represents a vital and interdependent balance of cultural norms and local biodiversity that have defined the configuration of the landscape in this region for thousands of years. Bees and Maya livelihoods and territories have been subjected to several injustices and power relations at different scales to which the Maya continue to exert resistance today. In the face of the increased loss of native bee populations, and unprecedented environmental devastation, this project examines the current situation of Maya stingless beekeeping within Maya communities of the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico, voiced by the guardian heirs who have cared for the stingless bees Kó‘olel Káab for generations.

[Fig. 2] Low deciduous forest in the state of Quintana Roo, Mexico. Photo: Veronica Briseño Castrejon

Aims and Objectives

This research project is geared towards enriching our cultural understanding of the practices and influences surrounding Maya stingless beekeeping in the cultural landscapes of the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico. It examines both documents of archaeological evidence and contemporary traditional Maya stingless beekeeping practices, especially with the stingless bee Ko’olel káab or Xúnan káab (Melipona beecheii)

In collaboration with traditional stingless beekeepers, this qualitative ethnographic and participatory design project aims to determine critical environmental design principles of Maya stingless beekeeping. The ultimate aim is not only best help preserve its multiscalar ecology for a sustainable future in this region but also to recognize this Maya cultural legacy from the original heirs and contribute to Maya self-determination.

Methodology

The study Unveiling Meliponiculture: Decolonizing Maya Stingless Beekeeping in the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico follows a qualitative and critical ethnographic methodology.

Maya stingless beekeeping is addressed from the environmental design perspective including different levels of meaning and activity systems concerning space, daily cultural materials, dwellings, landscapes, cosmogony, and the political ecology placed in context.

This environmental design research is informed by the methods and modes of analysis of Environment Behavior Studies [3,4] that help us to understand the meanings of built space at different scales, and ethnoecology [5] to explore how stingless beekeepers perceive and appropriate nature through their practices and purposes.

The methods followed in this study are documentary research data collection, ethnographic participant observations, semi-structured interviews, workshops, and participatory design with the close and continued insights of stingless beekeepers during the research process.

Stingless beekeepers are the main participants in the study however, we also included insights from traditional Milpa farmers, spiritual guides and healers, midwives, Maya women and children, and some defenders of the Maya territories.

Outcomes

During the fieldwork research of this doctoral study, it was possible to extensively explore the Campeche, Yucatan, and Quintana Roo states that comprise the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico. More than fifty Maya communities were visited to have encounters, informal conversations, interviews, and activities with different stingless beekeepers. This work throughout the region helped identify the localities where the scarce traditional Maya stingless beekeeping, as was practiced by the elders, still endures. Consequently, the ethnographic work, participant observations, and other methods were focused on and delved deeper into the diverse stingless beekeeping activities within the Maya zone of the Quintana Roo state.

[Fig. 3] Localities explored in the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico, focusing on the area of ethnographic work.Map adaptation:: Veronica Briseño Castrejon

Staying in several Maya communities allowed me to participate in the daily life of some families, and learn about the Maya traditional practices with the ko’olel káab bees as well as agriculture, rituals, and ceremonies. I engaged with diverse kinds of stingless beekeepers, Aj men (spiritual guides, healers), traditional milpa peasants or ko’olnáal, Maya women, midwives, and children. Also, I had conversations with Maya activists and defenders of their territories.

The relationship between the ko'olel káab bees (Melipona beecheii) and contemporary Maya in the Yucatan Peninsula primarily takes place within the enclosure of their homes. According to a Maya beekeeper, ko’olel means “first true woman”, and the word káab encompasses meanings such as bee, honey, hive, Earth, and the universe. For the Maya, ko'olel káab bees have not only been considered their alaak, their companions, but also sacred or saint beings. The Aj-Men Don Tomás refers to them as “Santas ko’olel káab”.

[Fig. 4] This image captures the interior of a hive of the ko’olel káab or Xúnaan káab bees (Melipona beecheii) Photo:: Veronica Briseño Castrejon

The ko’olel káab shares the same space with humans. Inside their hives made from hollowed logs or jobon, the bees are protected under a simple wooden structure covered with a palm roof known in the Maya language as otoch káab or najil káab. This structure is very similar to the house for the Maya and is typically located in family backyards commonly referred to as “solares" in the region. Traditional Maya dwellings are enclosed by “albarradas” which are low fences made of piled stones and used as an ancient structure and technology.

[Fig. 5] Traditional najil káab or Otoch káab ( Beehives’ house) have various characteristics in their design, form, size, and materials. However, they preserve almost all the materials from their vernacular design. Photos:: Veronica Briseño Castrejon

It is in the najil káab where an intrinsic relationship is maintained between the bees and their Kaabnáal, the person who daily strengthens the ancestral bond with the ko'olel káab.

The utterance Kaabnáal embraces a profound meaning that could be translated as “bee-man”. A kaabnáal is knowledgeable about all the ecological activities with the ko’olel káab including agriculture, traditional medicine, and construction of vernacular architecture.

[Fig. 6] Margarito Tuz, Pedro Cahun, and Pablo Dzib are káabnal traditional stingless beekeepers. Photos:: Veronica Briseño Castrejon

The Kaabnáal conducts different activities regarding the care of the ko’olel káab beehives such as cleaning the traditional jobon beehives, harvesting honey, pollen, and wax, creating a new beehive, or transferring them from modern boxes or trunks to jobon ones. Their traditional knowledge is based on their close observations of bees and the environment and the humble respect and practice of their ancestral beliefs. There are a few elderly stingless beekeepers left in Maya communities. Unfortunately, many of them have died without passing down their wise knowledge to their offspring.

[Fig. 7] Pablo Dzib (Kaabnáal) and Don Tomas (Aj-Men) with Veronica Briseño in the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico. Photos: Veronica Briseño Castrejon

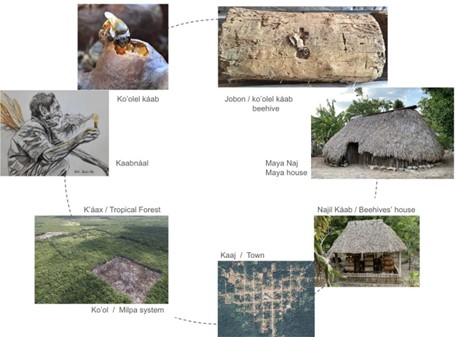

The traditional knowledge of stingless beekeepers possesses different levels of meaning at several scales. These scales go from the bee and their beekeeper to the traditional jobon beehives and the najil káab house that protects them, Maya dwellings, towns, traditional Maya agriculture, and the scale of the tropical forest. This study addresses these scales to understand Maya stingless beekeeping activity systems and their levels of meaning integrally:

[Fig. 8] Scales addressed in this research with traditional kaabnáal stingless beekeepers. Photos: Veronica Briseño Castrejon

The Milpa Maya or ko’ol is a diverse agroforestry polyculture system that integrates profound ecological knowledge including itinerant slash-and-burn agriculture. The Maya have worked with this system creating and sustaining the tropical forest for millennia.

Varieties of corn, squashes, and beans are some of the main species in the Milpa. The ko’olel káab take pollen from maize to nurture their families and multiply their brood. The ko'ol is essential for the Maya and the ko'olel káab. In the Maya cosmogony, Maya women and men are made of corn, and the rituals and ceremonies for their fields are celebrated with honey, incense, and wax from the ko’olel káab.

[Fig. 9] The Maya Slash and burn milpa agriculture which is an ancient practice. Gabriel Tuz is in his milpa area after the fire. Among the participants in this study are traditional peasant ko’olnáal or milperos like Gabriel, Mauro Dzib, and Don Hilario. Photos:: Gabriel Tuz and Veronica Briseño Castrejon

In Maya rituals and ceremonies for the ko’olel káab the sacred sakab corn drink is essential. During some of these events, a table is set with different elements in front of the beehives, close to the bees’ house najil káab. Special plants, flowers, corn drinks, chocolate, stingless bee honey, chal or incense from stingless beehives, and wax, are present in ceremonies devoted to the guardians of the tropical forest and the ko’olel káab.

[Fig.10] These photos illustrate some moments of the ceremony or loj: “the meal for the bees” U hanli káab. Honey is hung in containers from surrounding trees and is offered to the spirit owners of the tropical forest yúum tsilo’ob and yaj kanul balam’ob” Photos: Ángel Hau Dzib

Maya stingless beekeepers protect their beehives through several rituals or ceremonies such as jets’ lu’um for the settlement of a najil káab (beehives’ house), sakab offering for the blessing of the bees (corn drink with honey), u hanli káab (the meal for stingless bees), and K’aax naj (tie up the beehouse). The káabnal (stingless beekeeper) and the Aj-Men (spiritual guide) are present in most of these intimate events where only men can participate and with some exceptions women, including myself.

In special circumstances, women also take care of stingless bees. However, traditionally, Maya women have other important duties with them. Women mainly help in the kitchen to prepare the food for the families, and ceremonies, and support all the activities related to the domestic space with children and elders. Similarly, the ko’olel káab put the honey and pollen inside their jobon, nurture and feed their brood, and their mother; they help each other with various tasks inside the beehive.

[Fig.11] In this image women are “torteando waj”, or preparing tortillas for a ceremony devoted to the ko’olel káab. Furniture is traditionally designed according to the way of life using three stones for the fire to cook all kinds of meals with corn. Women include stingless bees in their beautiful embroidery to decorate the table as an altar. Photos:: Veronica Briseño Castrejon

Conclusion

All Maya rituals and ceremonies in every scale, from the stingless bee ko’olel káab to the beehive, their bee house, the Maya home, the community or town, and the milpa to the tropical forest, include elements taken from the stingless bees. Every scale is linked to the others in an interdependent and symbiotic reciprocity and balance where some Maya families still pray, wish, and make promises for their health, well-being, and harmonious life with stingless bees, their guardians, and milpa crops.

Ko’olel káab wild nests are very hard to find due to increased deforestation, their looting from the jungle to be sold, and the dispossession of ancestral practices with an economic and industrial approach to their honey, wax, and propolis promoted by meliponiculture practice.

[Fig.12] Wild nest of ko’olel káab (Melipona beecheii) in Quintana Roo, Mexico. Photo:: Veronica Briseño Castrejon

Ancient jobon beehives and najil káab houses are scarce in the cultural landscape of the Yucatan Peninsula. They are suffering transformations in their size, form, and materials. In many cases, they all have disappeared from the Maya communities due to different factors.

Maya stingless beekeepers report that there are many international and local organizations and foundations that interfere with the traditional way of life and practices of the Maya people. Some of them have appropriated their traditional knowledge committing biopiracy for profit, for funding diversifying their projects, and/or using Maya cultural practices as a tourist attraction supported by well-known international personalities.

There is increased deforestation for the implementation of several megadevelopment projects such as great areas for the settlement of solar panel farms, pork farms, agribusiness monocultures, transgenic soja, and corn, and the steady land speculation, and more threats derived from the recent project denominated “Maya Train”.

Also, in the view of Maya stingless beekeepers, there are entrepreneurs, non-profit organizations, foundations, hotels, and various projects that make use of greenwashing under the flag of sustainability, conservation, and the empowerment of women to the detriment of the Maya culture and the ecological life of stingless bees. The rise in popularity of the iconic Xúnaan Káab driven by these projects that promote the reproduction of their beehives and the sale of diverse products derived from their honey has been marred by overexploitation and increased commercialization of their wild nests plundered from the tropical forest.

However, the Ko’olel káab is the main stingless bee present in some traditional Maya backyards or solares. The Ko’olel káab still plays a fundamental role within the ethnoecological way of life of some Maya families, the endangered traditional milpa agricultural system, and the tropical forest. The traditional Maya stingless beekeeping practice mainly persists in a few places in Quintana Roo and Campeche states.

Among participants, there is a common agreement that more actions must be taken to stop deforestation and contamination at all scales from the development projects. There are specific cases where stingless beekeepers and apiculturists have deep concerns about the high loss of bees. All types of bees are dying due to the use of pesticides, and agrochemicals associated with monocultures and transgenic ones. Stingless beekeepers, traditional Maya milperos, and campesino wish the wise knowledge of elderly people would be listened to and included in the advice to projects that the Mexican government has been implementing in how to address agriculture in their territories. They urge us to come back to a respectful way to live with all beings on Earth.

Furthermore, and at the same level of importance, there is an overall concern about the loss of Maya self-determination, and the loss of interest among younger generations to stay in their communities to continue their cultural beliefs and traditions. This is mostly in the hands of the Maya people and fortunately, there are current Maya movements independent from

external organizations to recover and continue to strengthen their cultural identity. We are still working on some materials for them, reflecting the research.

How you benefitted from ECT funding

The possibility to conduct the last years of fieldwork research, thanks to the Eva Crane Trust has been essential for the continuation and culmination of this doctoral study. Without the funding, it would have been impossible to conduct such a comprehensive study, and the study sites would have been small in number.

[Fig.13] Don Godi and a prayer with Veronica Briseño going to a ceremony in the Yucatan Peninsula. Photo:: Carmen Chan

Maya stingless beekeepers and their families participating in this study, together with Citlali Hau Dzib as local interpreter and translator, and Veronica Briseño Castrejon, fondly thanks the Eva Crane Trust in this research project which recognizes the valuable knowledge of the Maya culture and relationship with the ko’olel kaab stingless bees at all scales and dimensions. I want to deeply thank Eva Crane Trust for their support and the trust placed in me and this study. Also, I want to thank my supervisor Dr. David Monteyne for his valuable support and guidance, and Dr. Elizabeth Paris as part of my Ph.D. committee for her continued support.

My special acknowledgment is to each Maya person who opened their heart and knowledge. My words will be never enough to express my gratitude for letting me live with them and share such beautiful days with their ko'olel káab in their dwellings. Thank you for letting me understand a bit about stingless bees and beyond through their eyes.

This research project has also received support from the Mexican National Council of Humanities, Science, and Technology (CONAHCYT), The University of Calgary, The School of Architecture, Planning, and Landscape (SAPL) of the University of Calgary, and the Calgary Institute for the Humanities (CIH) in Canada.

Veronica Briseño Castrejon,

University of Calgary

Ref.: ECTA_20210909

References:

- Crane, E. (1983). The archaeology of beekeeping. Ithaca, N.Y., Cornell University Press.

- Paris, E.H., Briseño Castrejon, V., Walker, D., Peraza Lope, C. (2020). The origins of Maya stingless beekeeping. Ethnobiology.

- Rapoport A. (1999) A framework for studying vernacular design. Vol 16(1) 52—64 in the Journal of Architecture and Planning Research pp.68-101

- Rapoport, A. (2006a) “Vernacular design as a model system,” in L. Asquith and M. Vellinga (Eds.) Vernacular Architecture in the 21st Century: Theory, Education and Practice, Abingdon, Oxon (UK), Taylor and Francis, p179-198

- Toledo-Manzur., (1992) What is Ethoecology? Origins, scope, and implications of a rising discipline. Ethnoecologica Vol.1 No.1 pp.5-20