The Fermanagh Wild Bee Project

The Fermanagh Wild Bee Project

County Fermanagh is located in the south west of Northern Ireland, being less than 10 km from the Atlantic Ocean at its closest point, which gives the County its temperate oceanic climate. It has an area of approximately 1700 km², with a diverse topography from extensive upland areas and low lying areas prone at times to flooding. Its most distinctive feature is Upper and Lower Lough Erne, which divides the County in two along its length. The waters flow from the south east, around the town of Enniskillen located at the nexus of the two Loughs, to the west where it enters the sea, west of Ballyshannon in Co. Donegal.

Local beekeepers generally favour our local indigenous dark honey bee. They are well adapted to our variable and at times wet summers. During the winter they cluster and the queen will usually stop laying for several weeks. According to research being undertaken by Professor Grace McCormack and her team at the National University of Ireland, Galway - the honey bee population across the country has bees that are consistent with being Amm, (the Dark European Honey Bee) i.e. no introgression (hybridisation) from other subspecies or hybrid/mongrel bees. (Hassett et al, 2018).

Background to the Project

In 2018 The Fermanagh Beekeepers Association (FBKA) commenced a 5- year project aimed at better understanding and supporting the wild or feral bee population. In recent years it had been thought that this population had all but disappeared due to the pressures associated with Varroa Destructor and the loss of habitat. Then we began to hear reports of colonies living in the wild, or more commonly in old buildings, with accounts of chimneys being occupied continuously for decades. There was an anxiety that the wild population could be a repository of disease but these accounts seemed to suggest that colonies living beyond the management of beekeepers were surviving in spite of the pressures and without any human intervention. (A sample from a swarm we collected in 2019 from a colony that has occupied a chimney for a number of years was assessed for disease burden by Northern Ireland’s Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute (AFBI). The assessment showed it to be free of acarine and nosema, with no evidence of Varroa or deformed winged virus. The swarm is now a well established colony from which we aim to produce daughter colonies in time, to assess their characteristics, long term health etc.)

The Wild Bee Project was conceived as a way of trying to better understand the wild honey bee population, to gain some understanding of why colonies seem to thrive in spite of pressures of parasites, disease and habitat loss, and to see if modest interventions in the form of providing suitable nesting sites could encourage and support the build up of the wild population. The location and preferences of swarming bees are themselves worthy of reflection. For instance, chimneys are reported often enough to suggest that the conditions therein appeal to bees, conditions that include dimensions, distance above ground level, the location of entrances, the presence of soot, air circulation, insulation and such like.

A search of literature of the optimum conditions for, and sizes of nesting sites for bees living in the wild was undertaken. With some modifications the Association settled on a wooden cuboidal box built in line with the conclusions reached by Seeley (2019). Suggestions and comments from Jonathan Powell (trustee of the Natural Beekeeping Trust) and David Heaf (beekeeper from northwest Wales, author, translator, retired biochemist) helped with some of the finer details. A pilot box was built, located in a tree in the summer of 2018 - and, in accord with Seeley’s findings, with the entrance hole approximately 21 feet (6.4m) from ground level. Within 4 weeks a small caste swarm occupied the box. By the end of the year the swarm had perished.

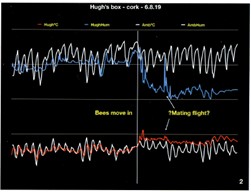

Monitoring how bees use the boxes

In thinking about our project at an earlier stage, we envisaged placing hives in old wooded areas - most of which we anticipated would be in relatively remote or not readily accessible locations. Thought was given on how we might monitor the boxes - remembering they would be over 6 m off the ground, and that the boxes were not designed to be opened once installed - on the principle that we wanted to see how bees survive in the wild without human intervention. We decided that some kind of sensor that would collect information about the internal temperature of the boxes could be added to a small number of boxes to provide us with data. This would enable us for example, to review how the bees seem to manage over the winter months. A search for a suitable device identified a bluetooth sensor with a datalogger that captured temperature and relative humidity. (This had been originally designed to track food stuffs in transit.) One of these had been installed in the 2018 pilot box and the arrival of the swarm in the summer showed a distinctive spike in temperature. A comparison with data from a matching sensor/logger placed in a Stevenson’s screen, which was capturing ambient data, showed that after the swarm settled in, the temperature remained a number of degrees higher thereafter. With both sensors, there were slight movements up and down to reflect the changing temperature throughout the day. What caught our attention was how the relative humidity dropped after the swarm moved in, again compared to the ambient data. This was a surprise as we expected the humidity measurement would rise given bees are breathing living beings and the water vapour from nectar and honey (with the increased temperature) would surely have increased, rather than decreased, the humidity. We need to better understand what is happening here.

The death of the colony at the end of 2018 was reflected in data which petered out to levels more or less equivalent to the ambient data. It was hard to see when precisely the colony could have been pronounced dead.

Following this experience, and with the support of the grants from the Eva Crane Trust, nine more boxes were built in early 2019. The grants enabled sensors to be added to all the boxes and enabled us to acquire a thermal imaging camera which provided valuable additional information (see picture). This equipment, along with visual observations, formed the main methods for monitoring the boxes.

One of the boxes was made of cork (40 mm thick) which has thermal conductivity in board form of about a third that of softwood. All had been placed by mid-May, eight in trees in older woodlands and one in a garden on a stand. We received enthusiastic engagement from the local National Trust properties, the RSPB (Royal Society for the Protection of Birds) which helped us place one of the boxes on a wooded island on Lower lough Erne and private landowners interested in the project. By the end of the swarming season, four out of the ten boxes in place had been occupied by swarms - two within 10 and 11 days of being installed. The sensors generated very useful and interesting data, repeating and extending the data from the 2018 pilot box. By the end of the year (2019) one of the colonies had perished.

(Left) One of the Feral Bee Boxes in situ. (Right) Chart showing the temperature (red) and relative humidity (blue) from one of the boxes. The White line shows the ambient temperature. Three are spikes when the swarms move.

Wild, feral or managed?

Approximately 50 of the active bee keepers in the County are members of FBKA but we do not know the total number of bee keepers in the study area. As noted, we also know of wild colonies living in buildings mostly, and then there is the unknown number of colonies living in the wild. So we really do not have any way of knowing if swarms arriving at our boxes are truly from wild stock, from feral stock (i.e. from a colony that was initially a swarm from a managed beehive) or from managed stock. For simplicity’s sake we refer to the bees occupying the boxes as wild bees - hence the title of the project.

Conclusions

It is too soon to say if this is an effective way of supporting wild bee populations but the first year’s experience, which has turned out to be a pilot study in itself, shows promise. We found it remarkable that four out of ten boxes were occupied in the 2019 season and in the case of two of the boxes, so soon after they were installed. The death of one colony we think reflects what must happen when bees are left to their own devices without the additional help of sugar syrup or fondant, which they might usually be given by beekeepers in a managed apiary. The drop in relative humidity, which was revealed across all occupied boxes, is a matter we would like to find out more about - mindful that the observation might just be an artefact of relative humidity itself, which is a measure of water vapour relative to the temperature of the air. If it is a real effect, how do the bees manage to lower the humidity?

The boxes were designed in accord with the summary below, and it is too soon to say if this is a ‘good enough’ design. Given bees occupy all sorts of voids in walls, trees etc. which appear to be of various formats, we are hopeful the design will be sufficient for the duration of the project.

The wooden boxes are heavy and not easily placed in trees. The cork box was very simple to install but it is more expensive to build and we do not know yet if the bees will like it in the long term (the cork box was one of the four occupied in 2019). In 2020 we will experiment with placing the boxes up on poles - as an alternative method of getting the boxes up to a suitable height - albeit lower than they might be if placed in trees.

One rewarding outcome has been the wider interest of the partners, including those who have found us suitable locations for the bee boxes. It is clear from the response to the Project that it has caught the imagination of other agencies and organisations, schools, families and individuals. The ability to produce data has been an added benefit in trying to communicate the life of the honey bee to our local community and has been received with considerable interest.

Looking ahead

This is a five-year project and the plan is to place more boxes in woodlands in 2020 and beyond. The 2020 boxes have been built with the help of the Men’s and Women’s Sheds in Fermanagh. These are local workshops that help individuals maintain connections and friendships through physical, educational and social activities. The Sheds have also made a number of

willow skeps with the help of a local basket maker, which we plan to cover with daub and experiment with as a low cost option, to see if they will offer suitable homes for wild colonies. The outcomes of the Wild Bee Project are also shared with a partnership of pollinator groups that includes the Fermanagh Beekeepers, which is convened by the Lough Erne Landscape Partnership (one of the UK’s National Lottery Heritage Fund’s landscape partnerships.) The Partnership is taking steps to improve habitats for pollinators in the County, which resonates well with the Wild Bee Project.

Disappointingly, the selected sensors began to fail towards the end of the first year of use. We had understood they should operate continuously for 5 years. The reasons are not clear as they were housed in a dry void (quilt) filled with wood shavings above the brood chamber. We are currently trying to source suitable alternatives that will give us data over the remaining lifetime of the project. It is disappointing that in spite of a good start, we will have a break in data from most if not all of the boxes erected in 2019. That said, it is not intended that every box will have a sensor. We just want enough to give us a useful data set from which we can derive information on how best to support the bees.

The Project is providing an insight to the life of the honey bee. It is reminding us of things that had been forgotten or which have yielded to more intensive beekeeping practices. It has reminded us that there is merit in living and working with honey bees in ways that are in sympathy with their instincts.

Through this project we aim to support the local wild honey bee population which amongst other things will provide a richer source of locally adapted queens and drones. The concern of recent years that, with Varroa, the honey bee could only survive in the future with the intervention of humans is being challenged. The rediscovery of a thriving wild bee population is such a source of encouragement.

Summary of key dimensions and design details of our first box

The box was designed to provide an internal volume for the bees of approximately 40 litres (as per Seeley);

38 mm thick unplaned softwood from a local mill was used to build the box. The following timber was used.

- Two narrower sides which fit within the overlapping two wider sides - 227 X 1600 mm

- Two wider pieces - front and rear - 303 X 1600 mm

- One base 227 X 227 mm

No glue was used. Self drilling steel-to-wood Tex bolts were used to attach the rear and front to the edges of the sides - 5 along each edge. Pilot holes were drilled first.

The 100 mm deep void (or quilt as per Warré principles) was fashioned at the top of the box by putting in a suspended ceiling. Untreated pallet wood was used for this. Wooden starter strips rubbed with bees wax, to which the bees could attach their comb, were placed at approximately 35 mm apart under the suspended ceiling.

A hole (25mm) was bored in the centre of this suspended ceiling and covered with a piece of Varroa screen.

As in this case a sensor was being added, it was placed just above this hole on a bracket which allowed air to flow upwards from the main chamber through the Varroa screen.

The void was loosely filled with untreated wood shavings, covered with hessian which was then stapled to the top of the box.

Before bolting on the front, the bottom piece (floor) was inserted and screwed into the square of the box, the inside of the box was scorched, about 5-6 short spales (short pieces of wood about 120 mm long - to help support comb and made from dowel) were inserted into previously drilled holes - on each side and/or rear, and a piece of old comb added to attract scout bees.

[Note: It was best to attach the two sides to the rear in the first instance, then build the suspended ceiling, attach the sensor (if being used), add the spales, and the old comb.]

A 25mm hole was bored midpoint in the front, about 200 mm from the top, with five 10 mm holes about 100 from the bottom.

An overlapping waterproof roof was fashioned from wood, covered with a non-metallic inert waterproof material.

Two strong screw eyes, that could carry the weight of the box, were screwed into the sides midpoint - and about 400 mm down from the top. These were used to lift the box and to help attach it to the tree on which the box was located.

A cherry picker was used to place the box in its tree. It was placed on a strong branch and it was lashed to the tree using two 25 mm ratchet straps.

Acknowledgements

The FBKA expresses it warmest thanks to the Eva Crane Trust for its financial support without which the project and the progress made to date would not have been possible. Thanks are also expressed to the various partner organisations mentioned in the article which have enthusiastically supported the project.

David Bolton

The Fermanagh Beekeepers Association