Honeybees are famous for their waggle dance, a unique communication system whereby foragers inform nestmates about the location of food from the hive. Upon arriving back after a successful foraging trip, a bee dances a figure-eight pattern across the vertical honeycomb, composed of repeating waggle phases - where she rapidly waves her abdomen from side to side whilst moving along the comb - and return phases - where she returns to the starting position of the dance (von Frisch, 1993). Fellow nestmates following the dance (‘follower bees’) are required to detect the dancer’s orientation relative to gravity and duration of the waggle phase and translate this into a flight path with a direction relative to the sun and distance from the hive (a ‘flight vector’). Although scientists have studied the waggle dance for a long time, how followers obtain the signalled information has received comparatively less attention. Followers extend their antennae towards the dancer and experience repeated contact during the waggle phase, which has led researchers to hypothesise that the antennae must be important for the exchange of information (Gil and De Marco, 2010). However, there had yet to be an observationally supported account of how the dancer's movements could be sensed via such and processed by the follower into their own internal flight vector that they can use to navigate to the food.

In our work, we explored two main questions: (1) how can follower bees ‘decode’ the movements of a dancer into a flight vector that they can follow to the food and (2) whether we can design a paradigm to test the predictions of a prospective decoding mechanism against the real search behaviour of bees. The former has been published in Hadjitofi and Webb (2024) in Current Biology (DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2024.02.045)

Antennal positioning enables followers to decode the dance

We tracked the movement of nestmates whilst following dances using high-speed, high-resolution cameras that were filming an observation hive containing a colony of Apis mellifera mellifera near the Roslin Institute, Edinburgh (Scotland). We observed that follower bees were positioned all around the dancer and at various angles to her: from front on, side on, as well as behind (Fig. 1). While it has been hypothesised that nestmates could obtain the angle of the food by following directly behind the dancer (Judd, 1994), our data highlights that followers may often need to gather the signalled information from different and varying positions to the dancer. To do so, since the angle of the dancer’s waggle phase relative to gravity indicates the angle of the food relative to the sun, the follower must proportionally account for their own angle to the dancer to correctly estimate the direction of the food being signalled.

But, how could the follower detect the actual angle of the dancer relative to gravity from an arbitrary – and potentially changing – position? We tracked the antennae of nestmates when following dances and calculated the angle of the straight line connecting the base of either antennae to its tip relative to the midline. When a nestmate approached a dancing bee, they stretched out their antennae evenly from their midline, which were then touched repeatedly by the dancer as she waggled by. Notably, we observed that the position of the bees’ antennae were altered based on the angle of their body relative to the dancer. When positioned on the left side of the dancer, the left antenna was angled further away from the nestmates’ midline, whereas the right antenna was angled much closer. A similar but opposite effect was seen when on the right of the dancer, with a smooth transition in between (Fig. 1).

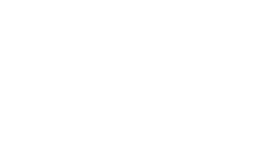

Fig. 1. Positioning of follower bees and their antennae when following waggle phases. Data from 47 bees across 59 total phases.

Top row, Left, A photograph of five nestmates surrounding a dancer. Arrows indicate how we measured the angles of followers’ bodies (blue) with respect to the dancer (grey). Right, Examples of stable and changing body angles of followers, plotted as a path over time relative to the dancer (pointing to 0° North on the plot). The path of each follower has been coloured by a measure of its Batschelet’s straightness index.

Bottom row, Left, A photograph of a dancer with labels showing how the positioning of her left (green) and right (pink) antennae are measured relative to her body angle (blue). Angles of the left antenna are denoted as positive angles from the midline and the right antenna denoted as negative. Middle, The angle of nestmates’ antennae when positioned around the dancer. Dots indicate the circular mean of the left and right antennae angles, along with the midpoint of the antennae (grey), computed across nestmates in 5° bins of angles to the dancer; the shaded area represents mean standard deviation. The directions of dancers have again been normalised to 0°. Right, Examples of real nestmates’ antennae when positioned at 45° (left), 180° (middle), and −45° (right) relative to the dancer.

Adapted from Hadjitofi and Webb (2024) under CC BY 4.0.

A neural circuit to recover the dance vector

This relationship could allow the nestmate to detect its orientation relative to the dancer, but how could this be transformed into a flight vector toward food? The central complex is a conserved region of the insect brain that is key in controlling oriented behaviours (Fisher, 2022). In our work (Hadjitofi and Webb, 2024), we proposed how a subset of central complex circuitry that has recently been identified in the fruit fly could also be involved in decoding the dance. Our key hypothesis was that a nestmate following a dance can use its antennal positioning to modulate its internal compass that tracks its orientation relative to gravity with connectivity patterns of the neurons that allow them to calculate the signalled direction of the food. The integration of this estimated direction during the waggle phase could enable the follower to obtain a corresponding flight vector towards the food. The details of the circuit are outlined in Hadjitofi and Webb (2024) (Fig. 2).

We implemented a computational model to simulate this circuit and used the real data from the tracked dance followers as input to obtain their estimated vector directions. We found that simulated nestmates’ estimated the signalled direction of the food more accurately when using antennal information than when estimating based on their own orientation (i.e. no antennal modulation). The circuit predicted that upon leaving the hive to search for the signalled resource, recruits would be distributed across the correct hemisphere containing the food. The accuracy could be further improved by averaging the vectors obtained from following consecutive waggle phases.

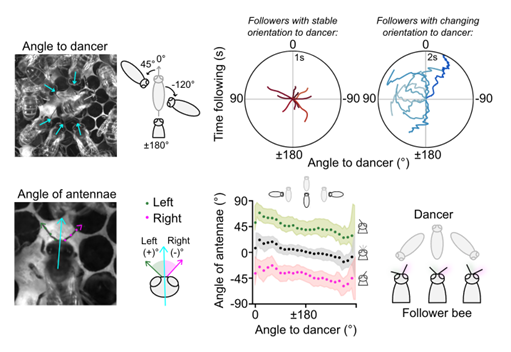

Fig. 2. A proposed model of the insect central complex that enables follower bees to decode the dance.

Top panel, A central complex circuit for followers to recover the angle of food signalled by the dancer. Top left shows a view of the bumblebee brain, with central complex neuropils illustrated in green (obtained from the insect brain database, www.insectbraindb.org). Shown are example cell activations in the proposed assimilation circuit for a nestmate positioned at -88° relative to the dancer. A full description of the circuit can be found in Hadjitofi and Webb (2024).

Bottom panel, Left, The predicted foodward vectors of followers relative to the dancer's mean waggle phase angle (normalised to 0° North on plot), as a result of feeding antennal positioning data to the proposed central complex circuit. Middle, The vector estimates during individual phases followed by four nestmates. Right, The foodward vectors from a nestmate following three consecutive waggle phases. Thin lines indicate the error at each time step; thick lines indicate the final vector for that phase; dotted is the vector that arises if averaging across waggle phases.

Adapted from Hadjitofi and Webb (2024) under CC BY 4.0.

A test of dance recruitment

To follow up this result, we devised an experiment to compare the predictions of the circuit with vectors expressed by real bees, inspired by the enforced-detour paradigm in ants. For example, by continuously updating their internal representation of their position through a process called path integration, a foraging ant that has been forced away from its direct route can reorient towards its original goal as soon as its path is unconstrained (Collett et al., 1999). Following a similar idea, we used patterned tunnels to control the foraging route of bees and impose an initial detour when returning foragers or new dance recruits attempted to navigate to it. The key prediction is that bees would adjust their flight path after leaving the detour to intersect their estimated location of the feeder. The angle of the bee’s trajectory immediately after the detour was thus recorded as a measure of how accurately they had estimated the feeder location. A random Julesz patterning on the walls of the tunnels manipulated the optic flow experienced by bees flying through them, causing them to perceive that they have flown a much greater distance (e.g., several hundred metres) than they actually have (e.g., six metres) (Srinivasan et al., 1996).

A mesh roof for the tunnel allowed the bees to maintain their sense of direction using the sky (Fig. 3). These tunnels enabled us to control the path taken to the known feeder as well as impose the detour in the test condition.

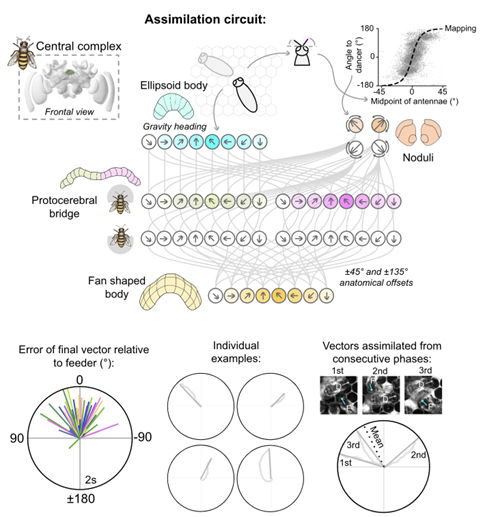

Fig. 3. Experimental setup detailing the components used in the detour study.

Top row, Relative configuration of training and detour tunnels tested during the experiment. F and vF respectively indicate the position of the feeder and its intended `virtual' position when forced along a detour.

Bottom row, (1), A view of the observation hive from the filming rig used to monitor dancing and following behaviours. (2) A tagged forager exiting the hive during the experiment. The specialised ‘bee tube’ entrance makes it easier to capture foragers and recruits as they leave the hive. (3) A forager flying through the patterned training tunnel with a mesh roof. (4) Tagged foragers around the feeder positioned at the end of the training tunnel. These tags were used to later identify the bees in the video recordings and relate their dance or following behaviour to their post detour flight angle. (5) View from the camera positioned on the ground to capture a bees trajectory post detour and an example measurement of the final flight angle (white).

The experiment took place over a couple of months at a site near Freie Universitat, Berlin (Germany). A group of bees were first trained to forage from a feeder that was positioned within a long training tunnel at a particular angle from the hive. Their dances and interactions with follower bees were then filmed upon returning to the hive. As a forager or a newly recruited follower was leaving the hive to begin its journey towards the feeder, they were caught and released into a shorter detour tunnel that was open at the other end. The angle of the bee’s trajectory as she emerged from the detour was tracked within a two metre area using the silhouette of the bee against the sky (Fig. 3). Interestingly, consistent with the general trends predicted by the central complex model, both foragers and recruits displayed a characteristic pattern of flight vectors, which were scattered across the expected hemisphere and centred on the intended location of the feeder (Fig. 4). This indicates that the relatively broad distribution of predicted flight paths predicted by the model may indeed be biologically accurate. For a sample of six recruits, we were also able to record their antennal positioning data for every waggle phase of a dance they followed, before their first attempted flight to the feeder. Comparing the model's predicted flight vectors to the real flight vectors expressed by the recruits revealed a strong correspondence between them, exceeding what would be expected if the model's predictions were random or unrelated (Fig. 4). These results further support the idea that it is possible to obtain a readout of a recruit's recovery of the signalled dance vector by modelling their antennal positioning data with the insect central complex circuit.

At the population level of the colony it may be advantageous to scatter recruits when foraging. However, an interesting question that this work invokes is whether the recruited nestmates that were predicted to deviate far from the feeder could, in fact, still find the advertised feeder. Afterall, historically, various studies have reported that recruits can successfully arrive at the intended feeder, even if it is only a small saucer located within a large field. Scientists have observed that ants and bees can use specific search patterns when they cannot immediately find their nest or a food source that they have been trained to (Wehner and Srinivasan, 1981; Reynolds et al., 2007). They search in increasing sizes of loops, starting and ending at the same spot, but facing different directions each time. This helps them cover a wider area and can deviate up to 30 to 50 metres from the original search point. Thus, it is possible that initiating a wide search centred on a flight vector that deviates from the food could still lead to its discovery, especially if there are pheromone attractants left by other bees around the target.

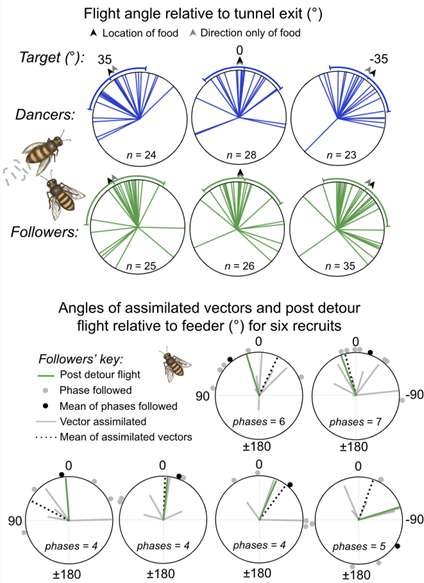

Fig. 4. The flight angles of bees attempting to navigate to a feeder following an imposed detour.

Top panel, Distributions of the flight angles post detour relative to the detour tunnel exit (at 0° North) for dancers (blue, i.e. foragers returning to the feeder) and newly recruited dance followers (green). The target angle indicates the angle we expect the bees to orient themselves if they had perfectly estimated the location (for three different detour angles).

Bottom panel, The predicted vectors of six new recruits and their subsequent angle of flight post detour, as a result of feeding their antennal positioning data to the central complex circuit (see Fig. 2). Lines indicate the vectors assimilated at the end of each waggle phase (dotted line indicates their mean), circles indicate the angle of waggle phases they had followed and green indicates their subsequent angle of flight post detour. All angles indicated relative to the feeder (normalised to 0°).

Acknowledgements

This work was conducted as part of my PhD at the University of Edinburgh, under the supervision of Prof. Barbara webb. The support provided by the Eva Crane Trust was crucial in enabling me to obtain the equipment necessary to perform the experiment, including Basler high frame rate machine vision cameras, lighting, and materials for the tunnels.

The final detour experiment took place in Berlin and was kindly hosted by Prof. Tim Landgraf and his lab group. Conducting this experiment would also not have been possible without Marie Messerich, who worked with me every day to train the bees and set up the tunnel experiment. We would also like to thank Dr Mark Barnett (Beebytes Analytics CIC) and Matthew Richardson (Scottish Beekeepers’ Association) for their all-round bee expertise and support providing the honeybee colonies over the summer seasons of my PhD. This research project has also received funding from the European Research Council (817535-UltimateCOMPASS awarded to Marie Dacke), as well as the Janet Foreman Fund (Scottish Beekeepers Association).

Dr Anna Hadjitofi, University of Edinburgh

Ref.: ECTA_20221208_Hadjitofi

Completed 2024

References

Frisch, K. V. (1993). The dance language and orientation of bees. Harvard University Press.

Gil, M., & De Marco, R. J. (2010). Decoding information in the honeybee dance: revisiting the tactile hypothesis. Animal Behaviour, 80(5), 887-894.

Hadjitofi, A., & Webb, B. (2024). Dynamic antennal positioning allows honeybee followers to decode the dance. Current Biology, 34(8), 1772-1779.

Judd, T. M. (1994). The waggle dance of the honey bee: which bees following a dancer successfully acquire the information? Journal of Insect Behavior, 8, 343-354.

Fisher, Y. E. (2022). Flexible navigational computations in the Drosophila central complex. Current opinion in neurobiology, 73, 102514.

Collett, M., Collett, T. S., & Wehner, R. (1999). Calibration of vector navigation in desert ants. Current Biology, 9(18), 1031-1034.

Srinivasan, M. V., Zhang, S. W., Lehrer, M., & Collett, T. S. (1996). Honeybee navigation en route to the goal: visual flight control and odometry. Journal of Experimental Biology, 199(1), 237-244.

Wehner, R., & Srinivasan, M. V. (1981). Searching behaviour of desert ants, genus Cataglyphis (Formicidae, Hymenoptera). Journal of comparative physiology, 142, 315-338.

Reynolds, A. M., Smith, A. D., Reynolds, D. R., Carreck, N. L., & Osborne, J. L. (2007). Honeybees perform optimal scale-free searching flights when attempting to locate a food source. Journal of Experimental Biology, 210(21), 3763-3770.